Bringing Harmony to Bustling Hangzhou: Archi-Tectonics Creates New Natural Landscape for 2023 Asian Games

Given its rectangular footprint and startlingly verdant, sylvan hilliness amid densely clustered tall buildings, Hangzhou’s new Canal Asian Games Ecopark invites comparison to New York City’s Central Park, especially when seen from above. But unlike Central Park, everything on view in the 116-acre (47-hectare) Ecopark—every building, tree, slope, hill and waterway—is brand new, or at least in a brand-new location.

Development of the park began in summer 2018 with three months of excavation and earthmoving that completely recontoured and restored the former agricultural fields, and continued with surreally fast foundation excavation and construction of new wetlands, an entire mall as connective valley, and several major buildings—all in time for the 2023 Games. The whole project was a tour de force of cutting-edge “zero-earth” earthmoving, BIM-optimized construction and sustainable design.

Impressive Numbers

“We used intelligent line-laying robots to automate earthmoving as we implemented the planner’s ‘zero-earth’ strategy,” says Deputy Chief Engineer Michael Huang of general contractor Xinsheng Construction Group. The total amount of earth excavated in the foundation pit of the underground square for this project is about 791,900 cubic meters. The total amount of earthwork excavated for the National Fitness Center and the hybrid Table Tennis Stadium is about 160,200 cubic meters, the earthwork excavated for the foundation pit of the tourist reception center is about 56,500 cubic meters, and the total amount of earthwork excavated in the foundation pit of the Field Hockey stadium is about 82,800 cubic meters. All the earthwork in the foundation pits needed to be used onsite. About 100,000 square meters of soil were used to create the high north and south slopes and hills, and the slopes needed to be covered with planting soil that was transported in.

“To do all this quickly, we determined the entire slope and boundary conditions, then performed slope layout and construction according to position information extracted from the BIM, set out through the intelligent line-laying robot,” explains Huang. “The entire recontouring process lasted 15 months.”

To get a sense of the quantities involved, visualize scraping 7.5 feet off the entire site and rearranging the scraped-off soil to create the hills, valleys, new islands and wetlands seen today. Also visualize relocating a 110KV high-voltage line, two signal towers and 3-meter main drain; removing, temporarily transplanting and replanting all the original site’s many trees; and removing and protecting bird nests and restoring them to their original location after construction.

A Major Feat of Urban Planning

The Asian Games are the world’s second-largest international athletics competition (after the Olympics), and the competition to plan and design the new Ecopark and its stadiums was intense. In 2018, the project was awarded to NYC-based multidisciplinary architectural design firm Archi-Tectonics, partnering with international landscape architects and urban designers !Melk, engineers Thornton Tomassetti, and local architects Zhejiang Province Institute of Architectural Design and Research and PowerChina Huadong Engineering Corporation Ltd.

The winning masterplan was built around three major concepts:

1. Transformation of the 1.6-kilometer-long site, bisected by a major road and river, into an active public Ecopark connected by a “shopping valley.”

2. Design several major new buildings, including the Field Hockey Stadium and the Table Tennis Stadium as well as a 23,000-square-foot fitness center and 18,000-square-foot exhibition center as hybrid buildings that would convert after the Games for public cultural use.

3) Implement the “sponge city” concept for sustainable, ecologically conscious development in one of China’s densest and fastest-growing cities.

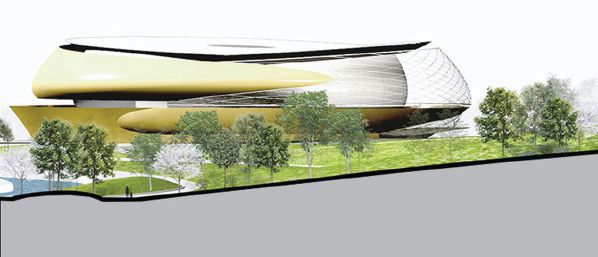

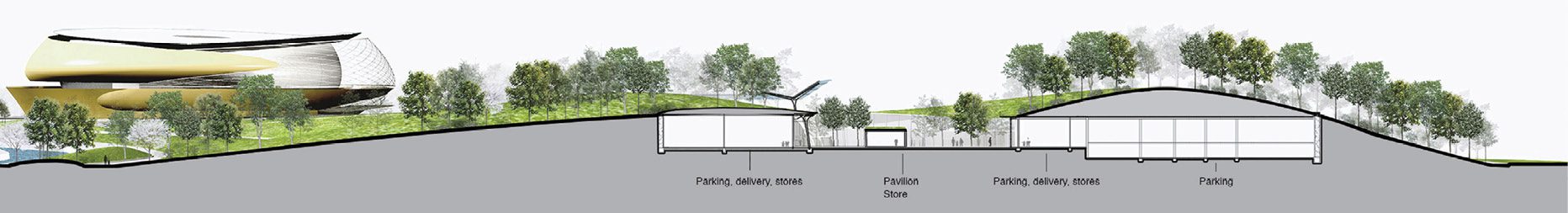

A sampling of 2D renderings provide a sense of the scale, vertical reconfiguration and urban setting of the new Canal Ecopark. (SFAP)

Excavating a Valley and Building an Ecopark

“Originally, the entire mall was supposed to be underground,” explains Archi-Tectonics Founding Partner Winka Dubbeldam. “Instead, we made it into a landscaped shopping valley with glass pavilions with green roofs, creating an open-air social core that feels connected to surrounding landscapes and city. We were challenged by the fact that the client requested only 15 percent of the project could be visible above ground, as 85 percent had to be park.”

This proposed modification of Hangzhou’s civic vision for the new Asian Games facility sounds simple but was in fact radical and required rethinking many aspects of the entire park design. For one thing, the “Eco” part of the Ecopark was threatened; an underground mall wouldn’t impact the intended surface appearance of a rustic natural landscape, but would need artificial lighting and cooling. The intended post-Games purpose of the Ecopark—to be a sustainable and restorative green city center—might be entirely defeated.

The Table Tennis Stadium built for the 2023 Asian Games will continue in use as a concert hall. (SFAP)

Aside from its utility as an athletic venue, the new Field Hockey Stadium is intended as a monumental outdoor sculpture. (SFAP)

It was the “valley” part of the Archi-Tectonics vision that saved the design, partly because a valley is inherently more environmentally friendly than an underground mall. “An underground mall would have required huge amounts of central air cooling and artificial lighting,” explains Dubbeldam. “The valley, of course, is far easier on energy requirements as it provides its own fresh air and daylight. And as we designed it, the valley also became more dynamic and livelier than traditional underground shopping malls.”

Put another way, the shopping valley as built isn’t simply a street or walkway connecting the field hockey and table tennis stadiums; it’s a green and winding destination in itself, served by two underground parking garages and featuring shops, restaurants, coffee shops and open-air communal spaces.

“Canyon” might be a better word than “valley,” as the 800-meter-long sunken open-air space is relatively narrow [70 meters wide (230 feet)] and lined with vertical glass shop walls—the shops being covered with green roofs that improve water retention and seamlessly extend the surrounding natural landscape. The earth excavated from the shopping valley is part of what made it possible to transform this formerly flat agricultural area into the hilly and biodiverse landscape it is today. And beneath the park, all the buildings and stadiums are connected by a 68,000-square-meter network of underground passageways, a theater and parking spaces.

A new overpass and viaduct route traffic and river over the created new “shopping valley.” (SFAP)

Dual-Purpose and Sculptural New Buildings

It might seem that an entirely new Ecopark consisting of a created valley and several new hills rising as high as 65 feet above original grade would hopelessly overshadow any other development here, but that’s not the case. Unusually, the two major buildings and the topography of the site they’re set on were designed at the same time, by the same design team.

“We entered the competition with landscape architects !Melk and structural engineers Thornton Tomassetti, so the design of the buildings and their structure—as well as the landscape—were designed as one holistic whole,” explains Dubbeldam. “In fact, all seven buildings that were part of the masterplan, and the entire Ecopark, were designed in one phase.”

Archi-Tectonics insisted that major buildings be intended for dual uses to ensure viability beyond the Asian Games. “Without a plan, projects like this risk becoming white elephants: unused, expensive to maintain and disruptive to a city’s fabric,” she notes. “Instead, we planned Canal Ecopark with Hangzhou’s future in mind, designing it to become a cultural fixture of daily life in the neighborhood, support continued urban growth, and make for a more sustainable and resilient city.”

As previously noted, the subgrade valley connecting the two stadiums meant sloping the park down and fitting out the space with the multiple amenities that make it a favorite retail destination. The Table Tennis Stadium was intentionally built with natural, maintenance-free materials and a hybrid seating system that can be configured into a 6,800-seat concert hall. The Field Hockey Stadium will continue in use for athletic events and other outdoor happenings such as outdoor cinema and concerts. The most eye-catching feature of the mostly open-air stadium is the sweeping translucent wing roof—its lightness and structural simplicity resembling a traditional oil-paper-and-bamboo umbrella.

“Working closely with Thornton Tomasetti, we prototyped and tested several iterations of the wing roof, finally arriving at this ultra-lightweight structure with a 410-foot free span,” she notes. Beyond the graceful, sculptural appearance, the stadium complements and suits—in scale and sweeping slope—the surrounding tall buildings of Hangzhou and new inclines of the Ecopark.

A serene new natural park in the midst of bustling Hangzhou. (SFAP)

Every City a Sponge

As befits a project with Ecopark in the name, this new city center had lofty environmental and sustainability goals and certifiably achieved them. The stadium and fitness centers having been granted the “Green Building Evaluation Label 3 Star” (GBEL 3 Star), the highest level of sustainability in China and equivalent to LEED Platinum. Some of this certification was due to BIM optimization that saved substantial steel and overall costs and shortened expected construction time 20 percent to just four years. But the lion’s share of sustainability gains is from Hangzhou’s (and China’s) absolute commitment to the “sponge city” stormwater management concept.

Sponge city is a uniquely Chinese take on stormwater management that relies on natural stormwater infrastructure and resembles urban practices worldwide such as Low Impact Development (U.S.), Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (U.K.), Landscape Stormwater Management (Denmark), etc., while not completely overlapping with any of these. It’s identified with Professor Kongjian Yu (the “Sponge Cities Architect”) who explicitly seeks to restore “tian-rén-hé-yi,” China’s ancient philosophy of harmony between people and nature.

“What we have done is totally wrong,” explained Yu. “We think we can use concrete to channelize rivers. We think we can use dikes to protect the city from being flooded, and we drain away all the water. Instead, we’re filling all the lakes to build a city, and that will cause flood and drought.”

The Chinese government is funding a major push to implement sponge-city ideals in 30 large cities—including features modeled on terraced rice farms, minimal concrete use, alternative water sources such as desalinated water and restored riverbanks—as part of a move to pervasive green infrastructure. Sponge-city concepts implemented at the new Ecopark primarily include the forested new hills, new bioswales and gardens throughout, 36,000 square meters of permeable pavement, the conversion of a small agricultural pond into a sizable lake with a wetland area of 74,000 square meters, and substantial restoration of riverbanks and wetlands.

“We even built small islands in the river to enhance flow and filter the water,” notes Dubbeldam. “Beyond stormwater management, all the hills and new forests and expanded wetlands soak up city noise, making the whole park a serene and nearly silent retreat.”

Amazing BIM

Site design, 3D digital design, BIM, model-based structural and MEP design, construction management, and additional CAD functions were all highly progressive and interoperable throughout the design phase and into operations. “We won a BIM award for our work here,” says Archi-Tectonics Architectural and LEED Designer Bowen Qin. “This was the first project in China where the landscape [including trees and plants] and slope design were carried out with full data interaction with the BIM design, and where MEP and other infrastructure design were coordinated through construction. That significantly reduced design and construction timelines, and we completed everything comfortably in time for the Games.”

“During the initial concept design phase, Rhino was the software for design because of its great parametric support and, along with Lumion, was all we used for our competition models,” he adds. “After we won, that work was translated to a Revit model, and we developed that with Rhino, Tekla, AutoCAD, etc., and all data was coordinated on the ProjectWise platform.”

This tour-de-force of sophisticated 3D tool use and interoperability was continued into the construction phase. “The contractor set up a special BIM management organization equipped with corresponding personnel, software and hardware resources, and a BIM office,” explains Qin. “The project team mainly used multi-software modeling and single-software integration for inter-professional collaborative management. On the basis of the design model, construction information was added, and the depth of the model gradually increased from LOD200 to LOD400 (Level of Development). Throughout construction, data was integrated and extracted for contractors, including onsite production progress, material procurement, material arrival, etc. Some CAD drawings were also used onsite to construct the buildings and park.”

About Angus Stocking

Angus Stocking is a former licensed land surveyor who has been writing about infrastructure since 2002 and is the producer and host of “Everything is Somewhere,” a podcast covering geospatial topics. Articles have appeared in most major industry trade journals, including CE News, The American Surveyor, Public Works, Roads & Bridges, US Water News, and several dozen more.